Northanger Abbey (Jane Austen): so much more than a satire on gothic novels

Rereading is such a joy. Especially Jane Austen novels. The layers I must have missed when reading Northanger Abbey at 18 are unbelievable!

In this episode:

🧑🎤 Jane Austen’s Kanye West

🙇🏽♀️ Sexist or advocate of gender equality?

🤦♀️Women can be rational, thank you very much

👋 Here I am!

🗣️But what’s my voice?

🤢 The hell hole called Bath. And the people. Oh, the people…

📖 Reading, the love of my life

The person, be it gentleman or lady, who has not pleasure in a good novel, must be intolerably stupid.

Above one of the Austen quotes I agree with most. However, dear reader, I have missed several clues of this gloriously sexist1 novel full of gender stereotypes for so many years.

A Gothic Dive into Northanger Abbey

This naive Catherine Morland had to dive into the blackness of Northanger Abbey for the 1st time at the age of 18. Nowhere near being married yet, but also nowhere near wholly understanding this story.

An apt choice for HEL it was, as our History of English Literature course was nicknamed at university. No one who reads ‘HEL’, would have supposed this to be fun. However, our professor included Northanger Abbey as a compulsory read.

Many (usually) male students whined about how boring this novel was. How one can dislike this hilarious novel, I understand less and less. Several gothic novels later, I can assure you: our professor actually did you a favour.

Rereading Northanger Abbey for the 5th time, I discovered it stands the test of time on so many levels. Unlike most of the gothic literature Austen mocks in this novel.

Yes, Mysteries of Udolpho, I am talking about you.

Here I am!

Never before did I spot the little clues that reveal Northanger Abbey also is about finding your own voice.

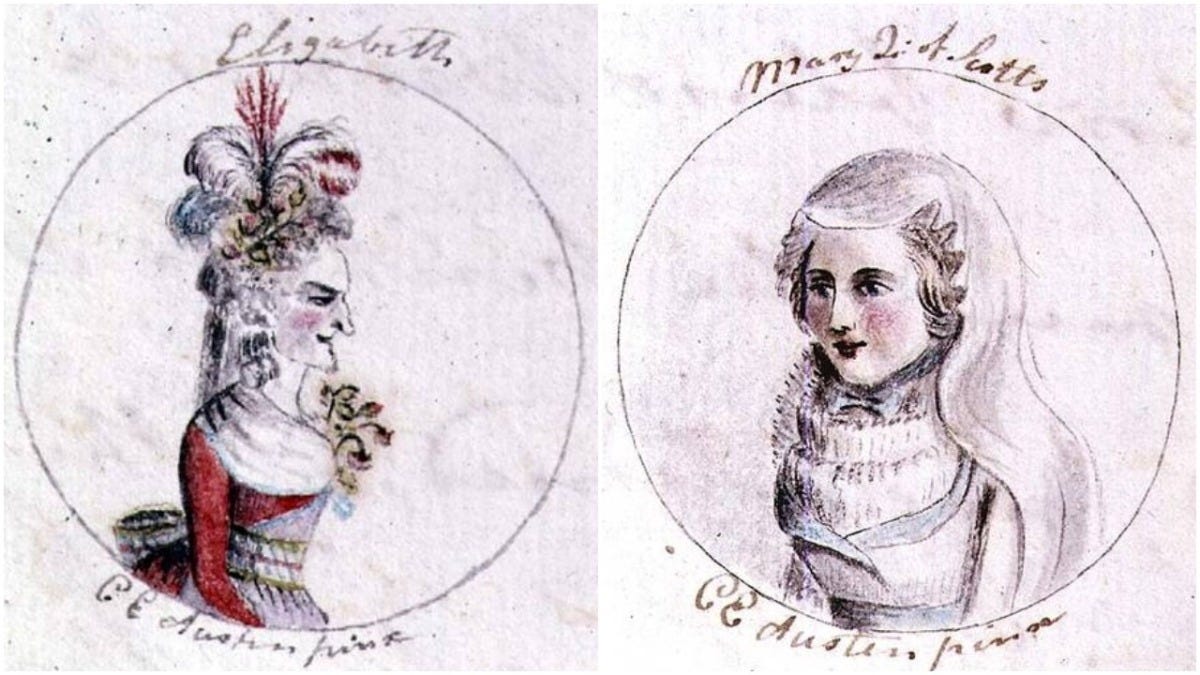

Characters like Catherine Morland and Henry Tilney are of course figuring out who they are and how they want to be in life. At the same time Austen is trying to assert her voice as a writer too.

From the opening paragraphs, as a matter of fact.

Going my own way

The novel starts quite boldly with Austen essentially saying, ‘I know what you expect of me as an author, but that’s not my plan. Expect something different.’

No one who had ever seen Catherine Morland in her infancy would have supposed her born to be an heroine. Her situation in life, the character of her father and mother, her own person and disposition, were all equally against her.

Her father was a clergyman, without being neglected, or poor, and a very respectable man, though his name was Richard2 — and he had never been handsome. He had a considerable independence besides two good livings — and he was not in the least addicted to locking up his daughters.

Her mother was a woman of useful plain sense, with a good temper, and, what is more remarkable, with a good constitution. She had three sons before Catherine was born; and instead of dying in bringing the latter into the world, as anybody might expect, she still lived on — lived to have six children more — to see them growing up around her, and to enjoy excellent health herself.

Austen immediately introduces her signature tone—mockery, sarcasm, and irony—as she overturns gothic conventions. It reminds me of the Dutch saying Al lachend zegt de zot de waarheid (‘While laughing, the fool tells the truth’).

She’ll never preach like some of her male contemporaries but instead uses humor and irony to make her points.

It’s the little things

Two little sentences stood out to me this time when Catherine Morland talks about books.

Injured body

In her famous defense of reading novels, Austen writes:

Let us not desert one another; we are an injured body

In the whole passage Austen critisises novelists who diss reading novels. Heroines should be seen reading. Criticism is for reviewers, Austen argues. We novelists need to defend and support each other.

Even though it’s naive young Catherine who utters these words, I believe Austen’s opinion extends to women in general.

The need for representation

Another sentence that struck me:

I read it [history] a little as a duty, but it tells me nothing that does not either vex or weary me. The quarrels of popes and kings, with wars or pestilences, in every page; the men all so good for nothing, and hardly any women at all — it is very tiresome: and yet I often think it odd that it should be so dull, for a great deal of it must be invention.

‘Hardly any women at all’, eminded me of children’s reactions to Encanto—thrilled to see themselves represented. Even in an offhand comment, Austen highlights how history excludes women. And that’s what she does throughout her books: she represents us.

The whole passage echoes Austen’s satirical ‘History of England’, one of her juvenilia in which she mocks history books. In this work she portrays kings and queens in short pieces that read like: One fact - boring - boring - this is what happend to his wife - he died.

And now for something completely different

If Jane Austen had been a 90s teen, her favourite band would have been Rage against the Machine.

Ans she rages in such a clever way. It’s naive Catherine who makes the subversive statement about women’s absence in history books, so conservative readers could brush it off. Yet, Austen is hiding her opinion in plain sight.

She even argues that novels show the way better than history books because they represent the world of women:

It is only Cecilia, or Camilla, or Belinda”; or, in short, only some work in which the greatest powers of the mind are displayed, in which the most thorough knowledge of human nature, the happiest delineation of its varieties, the liveliest effusions of wit and humour, are conveyed to the world in the best-chosen language.

Austen dedicates herself to showing women (and men), the choices they make, their reasons, and their consequences—so women can choose paths that lead to happiness.

Women can be rational, thank you very much

One of the statements in Northanger Abbey, is that women can be smart and rational

In this debut novel Austen shows us she is the queen of characterisation. A few brushstrokes paint a whole picture. Especially silly people are her forte.

Mrs Allen

I laughed out loud with her portrayal of Mrs Allen every time. It’s a lovely combination of show, don’t tell and add your own sarcastic comment.

[Mrs. Allen was] never satisfied with the day unless she spent the chief of it by the side of Mrs. Thorpe, in what they called conversation, but in which there was scarcely ever any exchange of opinion, and not often any resemblance of subject, for Mrs. Thorpe talked chiefly of her children, and Mrs. Allen of her gowns.

Scene after scene Austen shows us the intellectual poverty of Mrs Allen in actions and comments that show this lovely character doesn’t have a clue and deserves her own blogpost.

Isabella Thorpe

And yet, she lets you understand why these women behave the way they do. The best example in this novel is Isabella Thorpe.

Many critics are harsh on Isabella, but Austen subtly shows us her deeper motives by adding layers to the painting. She has no income and is desperate to climb the social ladder by marrying well. She’s learned—like some people today—that flattery and flirtation are tools for manipulation.

I at least feel some understanding for her. She’s an annoying friend, but haven’t we all had one like her at some point?

Dr. Octavia Cox shows you in this clip the genius of Austen’s characterisation by breaking down one paragraph, where Isabella can’t believe what time it is. Turning the mundane into drama, that’s her art. She’s the Regency equivalent of an influencer.

Austen, the little sexist

Apparently the University of Greenwich gave their students a warning that this book is full of gender stereotyping and sexism.

Apart from a blatant lack of sense of humour - the latter being a basic requirement for reading Austen - I do wonder whether the person issueing this label has actually read the novel.

Let us look examine some of the main male characters to expose whether Austen is guilty.3

Henry Tilney

Henry is such an interesting character. I always feel he is an imporatant vessel of Austen’s opinions (calling Mrs. Allen a picture of intellectual poverty) as well as what a men should be for her.

I just love how Henry pokes fun at himself. When speaking to Catherine, he tells her what she will write in her diary. With what I read about how Austen was, I can’t but think there is a lot of her in him.

“Yes, I know exactly what you will say: Friday, went to the Lower Rooms; wore my sprigged muslin robe with blue trimmings — plain black shoes — appeared to much advantage; but was strangely harassed by a queer, half-witted man, who would make me dance with him, and distressed me by his nonsense.”

I would fall in love straightaway.

At the same time, Henry Tilney is the one who guides Catherine with his sharp analysis and non-conformist views. On matrimony, he says:

And such is your definition of matrimony and dancing. Taken in that light certainly, their resemblance is not striking; but I think I could place them in such a view. You will allow, that in both, man has the advantage of choice, woman only the power of refusal.

On books, men weren’t supposed to like novels, although apparently Austen’s brothers did.

The person, be it gentleman or lady, who has not pleasure in a good novel, must be intolerably stupid. I have read all Mrs. Radcliffe’s works, and most of them with great pleasure. The Mysteries of Udolpho, when I had once begun it, I could not lay down again; I remember finishing it in two days — my hair standing on end the whole time.”

It’s also mentioned that he has an excellent taste in muslins, which he buys for his sister. On top of that he seems to be struggling with the alpha male behaviour of his father and his brother. So I’d say he is the opposite of a gender stereotype. Austen shows you there is more to men than just alpha males.

John Thorpe

Toxic, manipulative John Thorpe. The Kanye West of Austen’s novels. Makes me want to scream every time he speaks or acts in Northanger Abbey. Foil to the wonderful Henry Tilney.

Lies to Catherine about the whereabouts of Henry Tilney, cancels her appointment with the Tilneys behind her back -my god, that one makes my blood boil every time and lies to General Tilney about an impending engagement.

At first sight: John Thorpe is the epitome of a gender stereotype. Men are manipulative and will decide instead of us. However Austen shows you Catherine’s negative feelings. On top of that, she lets Catherine react to it. First passively by just being vexed when he doesn’t stop the carriage.

But when Thorpe cancels her plans with the Tilneys, she lets Catherine act by countercancelling. Catherine has grown into a person that makes her own choices and doesn’t let others govern her. Show, don’t tell what’s possible, Austen already realised the importance of that.

General Tilney

Admittedly I struggle a bit with this one. On the surface he seems to be redeemed of murdering his wife by Henry telling Catherine off for novels having influenced her mind.

But as Octavia Cox points out in this lovely video about the worst Jane Austen marriages, Henry’s defence of his father is rather poor and she surrounds him with words and deeds that conjure up the feeling.

But again, this character is about representation for me. She shows how a very unpleasant man makes both his wife, one of his sons and his daughters unhappy. That it hurts more people than just the women surrounding him.

Activist Austen

She shows us how genderaffirming men affect others. And not only women, but also men. And urges the (female) reader to use her power of refusal wisely.

I know I am putting on my 21st century glasses here, but for me Austen is an advocate of gender equality.

Social criticism

Bath, compared with London, has little variety, and so everybody finds out every year. 'For six weeks, I allow Bath is pleasant enough; but beyond that, it is the most tiresome place in the world.

It’s a truth generally acknowledged that Austen wasn’t a fan of the hellhole called Bath. How she loathes the superficiallity of the social acticities there. She laughs at people who cannot cross the street because of passing vehicles and consider it a drama. Judgements are based on impressions.

It announces another favourite topic of Austen: social criticism. I just adore how this book is one big announcement of what Austen as a novelist will be about.

Reading, the love of my life

Austen and I, we like the same men and often have the same opinions. We share a profound love for books. Maybe we love our books even more than our men.

Novels were the videogames of their time: the devil that was corrupting young people. Austen shows the power of the novel: books can guide us, help us grow, and make us better people.

And I couldn’t agree more!

According to some nitwits.

Being a massive Suede fan, this really makes me chuckle. Poor Richard.

I feel there is so much to say about this topic that I need to write a separate post on this later.